How to Use Neuroscience to Stretch Past Self-Imposed Limits

Photo by Sammie Chaffin on Unsplash

Let’s face it. Our brains are hardwired to avoid discomfort.

To our brains, discomfort is a threat.

In the face of stress, our built-in and hard-wired survival mechanism kicks in. Most times, avoidance (or flight from the fight or flight response) enters the equation.

Our brains evolved to be this way — that is, to avoid discomfort and stress. It’s a way to keep us safe and comfortable.

From our brain’s perspective, why would we purposely put ourselves in “harm’s way?” Why would we take on a risk like being out of our comfort zone? Being comfortable takes less effort, and our brains revel in this.

Being outside of our comfort zone is like taking a cold shower — uncomfortable and shocking to the system. Despite the discomfort, it’s also temporary, as many situations outside of what we perceive as “safe.”

Is it worth it to step outside of your comfort zone, even if discomfort is temporary? What if the benefits outweigh the discomfort?

Since the dinosaur era, certain parts of the brain evolved to keep us alive:

Areas that control breathing, our heartbeat, and body functions.

Areas that help us react to danger or threats.

These are the oldest parts of the brain. Daily, they help us survive. Without them, we wouldn’t be able to breathe or act in stressful or dangerous situations.

The discomfort we feel from being out of our comfort zone is produced in the amygdala — the area responsible for keeping us comfortable. It houses our emotions and evolved to notice negativity. So, any threat or uncomfortable situation causes our brains to go into survival mode for protection.

Our frontal lobe, including logic, decision-making, planning, and motivation, developed later. So, in distress, our frontal lobe is quieter, letting our emotions take the steering wheel. After all, our emotions are there to warn us of danger and to react. Like much of our brain’s work, the brain’s safety setting is automatic and sometimes out of our awareness.

Shockingly, this process, like many brain processes, is unconscious — beneath our awareness.

Recently, I wrote an article about unconscious processes — the many processes like storing memories that our brain completes without us knowing.

The problem with the automatic stress response is that it’s triggered even in situations that aren’t necessary. Like, when giving a presentation, going on a first date, driving over a bridge, or asking for a promotion at work. Doing anything new is anything but safe and comfortable. It comes with risk, stress, and feeling stretched. If people are too inflexible, they feel like they will break under pressure.

When starting something new, have you ever noticed the negative voice in the back of your head? It’s the voice that tells you that you’re not good enough, that you should just give up or try again later.

These thoughts seep into our heads and start to change how we act.

Because our brains avoid pain and discomfort, our decision-making can become impaired. This negative voice is our brain’s way of steering us out of harm’s way. From a survival standpoint, it makes sense. Our brains evolved to make decisions that move us away from the threat or stressor.

Noticing your response to your brain’s alarm system can help you know how to calm the emotional part of your brain.

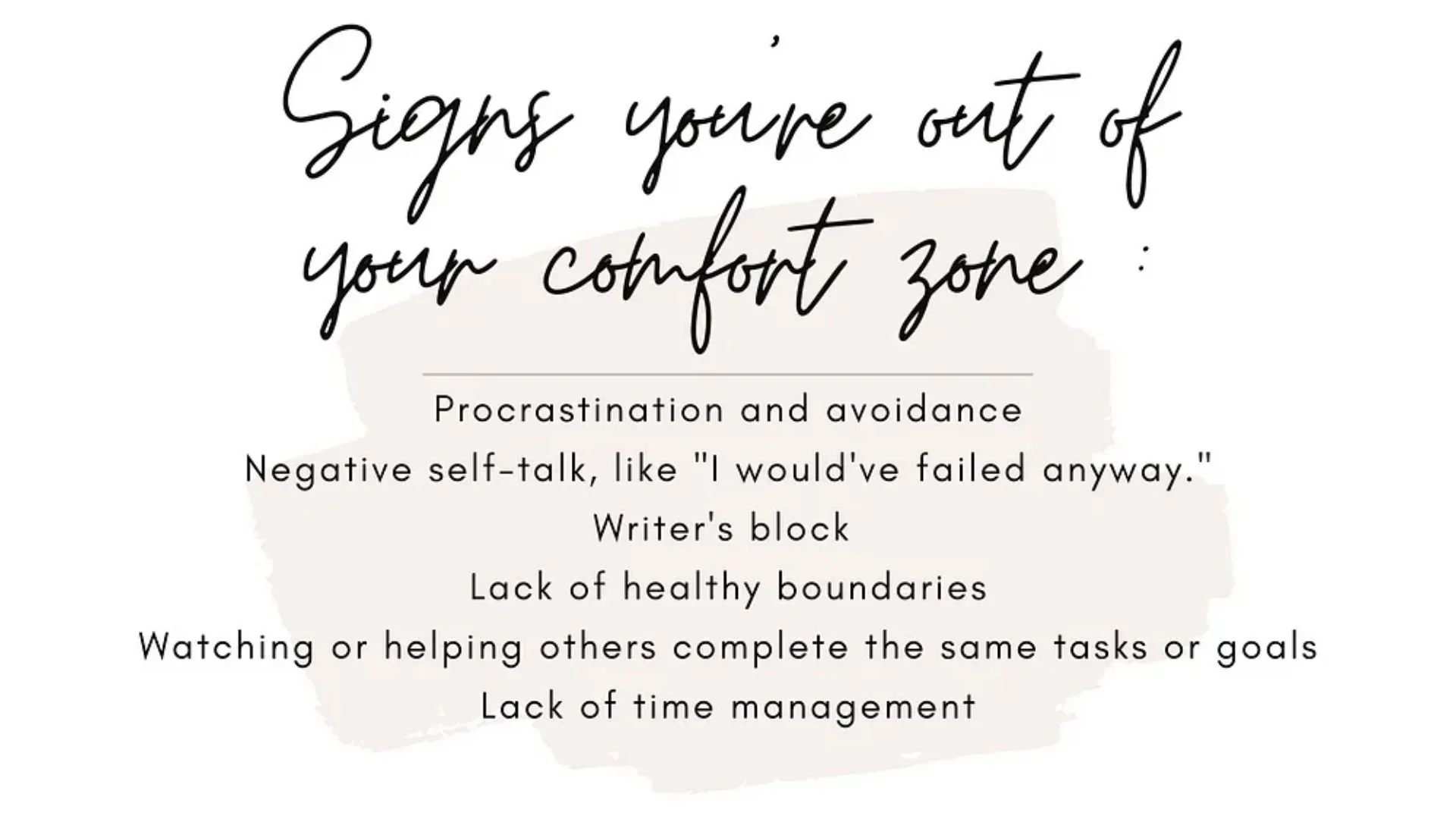

Sometimes, out of the “comfort zone” alarm bells look like this:

Train your brain to adapt —creating new neural pathways each time you go beyond your comfort zone or learn a new skill.

Even though we have stress responses that keep us safe, we were also born with the ability to create new connections between our brain cells. Use your frontal lobe, which houses logic, decision-making, and motivation, to calm your brain’s alarm system. It’s like a manual override of the human alarm system.

Decide over and over again that being out of your comfort zone is worth it.

Decide that your growth is worth more.

Move your brain’s response to stress from the unconscious survival mode to consciously approaching the edge of your comfort zone, peering out at the unknown and uncharted territory.

The more you approach difficulty and come out on the other side, your brain adapts and creates new neural pathways — the process of neuroplasticity. When you challenge the negative voice in your head, you also make neural connections between your brain cells.

Over time, each time you take a step out of your comfort zone, the neural connections will become stronger.

Odds are, your brain may have made some tasks seem too big or too uncomfortable. Show yourself and your brain that you can do hard things. At that moment, unknowingly, you will have created new connections between your brain cells.

Change is a threat to the comfort that our brain craves. However, the more you tackle challenges as they come, stretching your comfort zone, your brain will adapt. Over time, that challenge may not be difficult, at all.

You will adapt. We are adaptation machines.

But, many people have difficulty with adapting. Negative self-talk and fear make the brain’s alarm bells ring louder and louder. Survival mode is triggered.

Some people stop before they step outside of comfort. They’ve talked themselves out of changing or doing anything new. Their brains are good at keeping them safe, and they don’t challenge that negative voice. It’s a lot like living on autopilot, staying on a course even if that’s not the destination you want.

Others stop once they’re out of their comfort zones. Once they veer off course, they quickly revert to what’s safe.

The people who seem to be successful continually adapt — they approach situations that have uncertain outcomes and adjust along the way.

On your journey, challenges may arise. Here’s one mantra to say to yourself in these moments:

“I can do hard things.”

Like taking a cold shower, stepping out of your comfort zone will sometimes be uncomfortable, but you may surprise yourself. You may be more capable than you think when approaching that stressful thing you’ve been avoiding. I mentioned the mantra, “I can do hard things.” By saying this to yourself, you’re introducing a manual override of the automatic thoughts from your brain’s alarm system — a process called cognitive restructuring. By approaching stressful situations and encouraging yourself along the way, your brain will adapt.

I’m not writing this as just a psychologist, but a fellow human who experiences stress and fear. When I feel the alarm bells going off, sometimes I purposely do what I want to avoid. This is my way of training my brain to adapt. Over the years, I’ve noticed that I’m more resilient and not preoccupied with stress and fear.

Being out of my comfort zone is a temporary discomfort; my growth is worth more.

The science-backed way to take steps outside of your comfort zone:

Approaching the edge of your comfort zone requires “exposure.” No, not exposing yourself literally, but allowing yourself to come into contact with something that feels stressful…and doing it time and time again. By choosing to step outside of comfort over and over, something amazing starts to happen. What was previously stressful or uncomfortable becomes tolerable. It’s no longer a threat. The brain’s alarm system turns off. Psychologically, this exposure process helps through:

Habituation —over time, being less and less phased by something that was uncomfortable. It’s one of the most common forms of learning. Our brains learn to tune out what’s not essential. By stepping outside of your comfort zone over and over, habitation is the brain learning that it’s not a threat or something that should cause alarm.

Extinction — weakening the previously learned association between the stressful situation and our stress response. Since we were young, our brains associate certain things with our body’s response, often beneath our awareness. For example, when giving a presentation, you may become sweaty and tense. Your brain associates speaking with stress, even if no life-threatening outcome may happen. By approaching presentation-giving repeatedly, the learned response (i.e., freaking out) lessens and sometimes completely goes away over time.

Emotional processing — gaining new and helpful ways of looking at a stressful situation. Emotional processing lies in our memories, and if we learned to be fearful of a situation, our memories have interpreted the situation negatively. By taking steps out of the comfort zone, it’s like rewriting our brain’s meaning of fear and stressful situations — deprogramming old fears and through “exposure.” As a result, there’s less stress and new meaning and perceptions about previously stressful situations.

To get the ball rolling on this exposure process, start small. Is there a “low stakes” situation that feels uncomfortable that you can approach? One example of this can be setting boundaries with others in life. If you have trouble setting boundaries and limits with others, exposure may be saying “no” to that thing you typically agree to do. At work, instead of taking on additional tasks, one can say, “I’m not available to take that on right now. I can get to it by [insert day].” Instead of telling that friend that you’re available to help them move, you can decline but offer to buy a housewarming gift.

In your life, you may have other situations that provoke your body’s alarm system. Is there something small you can do to approach that situation? Taking these small steps outside of your comfort zone can grow the parameter of your comfort zone.